“Radical Words” – seems like a fringe call to action. That’s precisely what the historical documents (all originals) on display this fall at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, MA are – radical. They intended to fundamentally change the political order, and they did.

The Magna Carta is the touchstone of modern democracy and the U.S. legal system. It was signed in June 1215 by King John of England at Runnymede as a way to appease his land baron subjects who believed the King’s power had run amok, hoping to avoid civil war. The primary message of the Magna Carta is that no person is above the law. Despite this historic moment, the Pope (who was really in charge at the time and apparently was the law) nullified the agreement, and England entered into civil war.

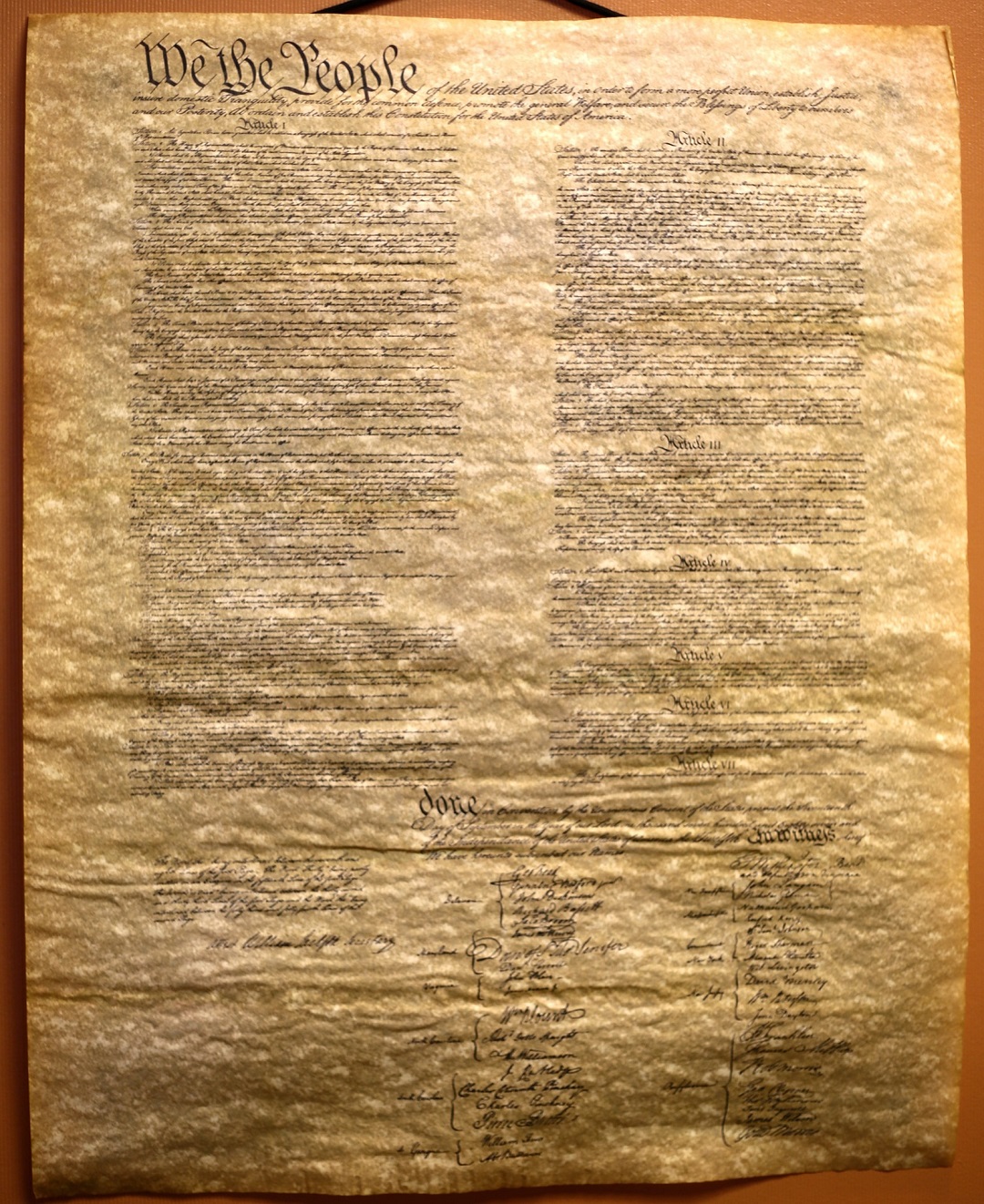

Much like the 13th century rebellious English subjects, the American Patriots used principles laid out in the Magna Carta to justify their actions in fighting the monarchy of King George III. The original copy of the Declaration of Independence on display at Radical Words is the only copy that is definitively associated with one of the signatories—Joseph Hewes, delegate from NC. George Mason’s draft copy of the U.S. Constitution, complete with his notes, illustrates how vigorous the debates were at the Constitutional Convention in 1787—Mason eventually refused to sign the final document.

The Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order issued by President Lincoln in 1863 as a means of keeping the rebellious states in the Union. While it set abolition of slavery as a goal, it did not free slaves or grant freed slaves their citizenship. This action was radical in that Lincoln did not request the approval of Congress, and it was clear that he hoped to fundamentally change the Union by abolishing slavery. Slavery was abolished 2 years later with the adoption of the 13th Amendment in 1865. Voting rights were extended to African American men (and other non-white men) by the 15th Amendment in 1870, although still today many states strategically prevent African Americans and others from voting.

The Rights of Women was signed by 24 suffragettes who presented, read, and distributed their words at the 1876 World’s Fair in Philadelphia, home to the Constitutional Convention. Women did not win the right to vote for another 44 years, until 1920 with the passage of the 19th Amendment. This particular document was very personal to me – my paternal grandmother could not vote until she was 40 years old, despite being born in the U.S. and working her entire life. My maternal grandmother turned 21 (at that time, 21 was the voting age) the year that women gained voting rights, and she voted in every election until her death. These were women I personally knew well who were disenfranchised and not considered full citizens due to the fact that they were women.

Finally, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was the first global declaration of human rights, adopted by the United Nations in 1948 following the atrocities of World War II. This document extends to all people the core human rights values set forth in the Magna Carta and enacted through revolutionary governments. Together, these Radical Words, from barons to patriots to slaves to women, are the roots of human rights; in each case considered radical due to their challenging of the status quo by demanding rights suppressed by those in power, whom were often born into privilege.