Leah Pope, Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow, Vera Institute of Justice

David Shern, Ph.D., Senior Public Health Advisor, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors

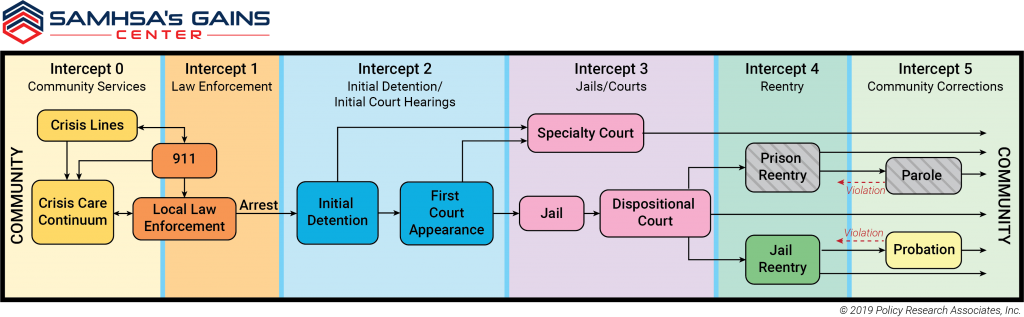

This article is part of a three-part series on how the criminal justice system can play a role in shortening the duration of untreated psychosis for people with mental illness who have become justice involved through the lens of the Sequential Intercept Model. Part one examines Intercepts 0 – 1. Part two examines Intercepts 2 – 3. Part three examines Intercepts 4 – 5.

Shortening the duration of untreated psychosis for individuals experiencing their first episode of psychosis (FEP) is essential. Linking these individuals to evidence-based programs that specialize in treating these conditions has been demonstrated to improve outcomes and may reduce the likelihood of a lifetime disability. Increasingly, these specialty programs are available throughout the United States through state and federal funding efforts.

Since people experiencing a first episode of psychosis may be in crisis, law enforcement officers are likely to encounter them. In the last GAINS newsletter, we addressed the use of Intercepts 0 and 1 of the Sequential Intercept Model to divert individuals from the criminal justice system and link them to specialty coordinated care systems or other appropriate specialty treatment programs. In this article, we will focus on the role of Intercepts 2 and 3.

Intercepts 2 and 3 are where people with mental and substance use disorders have been arrested and are going through intake, booking, and an initial hearing or are in jail before and during their trial.

When individuals with FEP are not detected in the first two Intercepts, they may be identified by screening activities conducted as part of their initial arrest processing, booking, or preliminary court hearings. The short window between arrest or initial detention and their first court appearance is an opportunity for a brief screening that can detect signs of psychosis. For those individuals who screen positive and give permission for their information to be shared, the screening data may be used to develop pretrial release recommendations and linkage to specialty services. Screening data may also be shared with family members, defense attorneys, or other advocates to facilitate linkage. The Enhanced Pre-Arraignment Screening Unit in Manhattan’s Criminal Court is an excellent example of how Intercept 2 can work. Screeners in this setting use an electronic screening tool to detect general health and mental health issues. With client consent, information from the screen as well as other information from administrative records can be shared with the defense attorney as well as correctional health authorities to ensure the use of appropriate care strategies.

Individuals whose problems are not detected in Intercept 2 or who do not qualify for diversion are likely to spend some time in jail while their case is being tried. Given these potentially stressful circumstances, it is vital that jails have the capacity to detect early psychosis and provide treatment that is in line with holistic, evidence-based approaches used in the community, including comprehensive assessments and care plans, targeted antipsychotic medication, and communication across providers and settings. While the jail setting is not optimal for initiating treatment, it can be used to begin the engagement process and early treatment planning that will be helpful in the longer term. Working with families and linking the individual to specialty programs may be beneficial, especially since many people will spend only a short time in jail before returning to the community. If a mental health treatment court is available, it may also link the individual with specialty care. Mental health courts may be particularly appropriate for individuals earlier in the course of illness who might be struggling with engagement with the mental health system.1

Representatives from the criminal justice system at different Intercepts are likely to encounter people experiencing first episode psychosis. Linking these individuals to effective care by diverting them from criminal justice involvement as much as possible may benefit both the individual’s long-term well-being and decrease their likelihood of further criminal justice involvement.

[1] Ford, Elizabeth (2016). First-Episode Psychosis in the Criminal Justice System: Identifying a Critical Intercept for Early Intervention. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 23 (3), 167-175.