Content warning: This blog post includes references to racially motivated violence.

Growing up in suburban upstate New York, I understood at a very young age that I was not white, but I didn’t feel Asian. Despite my parents’ colorblind approach to raising me, it did not stop the uncertainty and emptiness I felt about being adopted. I could not participate in class activities such as tracing inherited features, like nose shape and hairlines. There were times I didn’t know which bubble, “White” or “Asian Pacific Islander,” to fill in on my exam scantrons. Even though I was born in America, people would (and still!) ask me, “Where are you from?” “What Asian are you?” and “Do you speak____?” As I got older, people in my life casually described my features using racist slurs and referred to my “oriental feminity.” I was sorely unprepared for life as a transracial adoptee and struggled to navigate situations that confronted my race and identity.

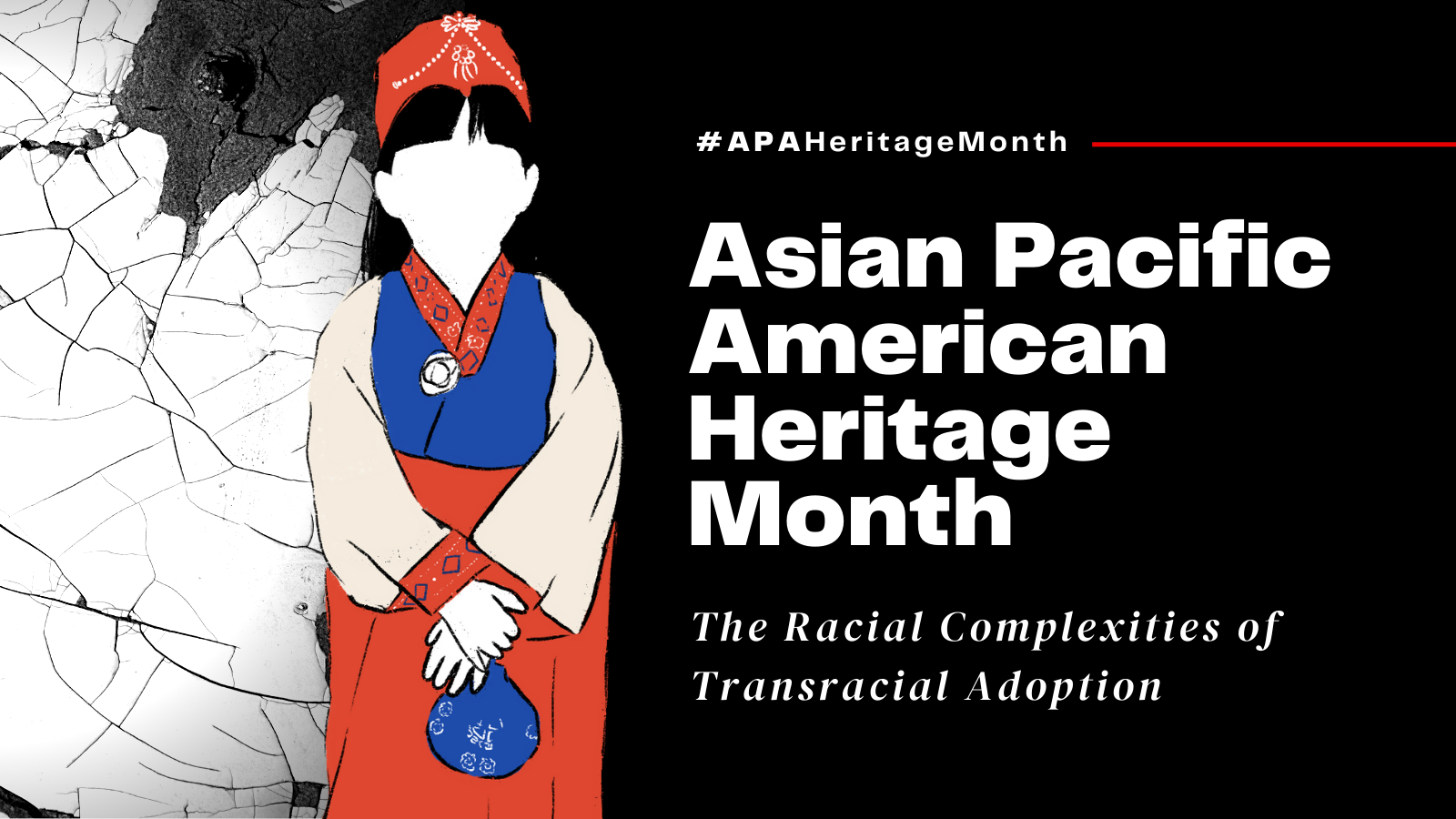

Being a Korean American indoctrinated into white society with no connection to my ethnic heritage made me feel like an outcast to both my white and Korean peers. I was once gifted a hanbok, but the inability to put it on properly or explain its significance filled me with so much shame. When I did have interest in experiencing Korean culture with my friends or family, it was often met with unappetizing refusal and comedic banter. These experiences exposed me as “other than” and worsened the insecurity I felt about my racial identity. At the time, I did not know others who could validate my experience or have the language to even describe what I was feeling. So, for a long time, I avoided acknowledging myself as a woman of color and instead would defend my limitations by stating I was adopted.

It wasn’t until college when I was first introduced to the concepts of intersectionality, implicit bias, identity, and trauma. These words sparked a transformational look at myself, and I began revisiting and unburying memories and experiences that overlapped with my race, gender, and sense of belonging. I always felt that curiosity about my origin was offensive and insulting to my parents, however, it was what I needed to begin racial healing. I let my curiosity lead me to books like The Struggle for Soy: And Other Dilemmas of a Korean Adoptee and several podcasts like Adapted, The Rambler and Adopted Feels. For the first time, they revealed to me that adoption was a form of trauma and many adoptees shared the same turbulent emotions I was experiencing. I found online forums with communities of other Korean adoptees on their own journeys of personal exploration and racial healing.

Like many people of color maneuvering through predominantly white spaces, I am trying to embrace my authentic self by reclaiming my own narrative, whether it be through my art, body, or relationships. Even though I am just beginning this journey, I feel a sense of liberation and immense gratitude for those before me who have paved the way for this dialogue to exist.