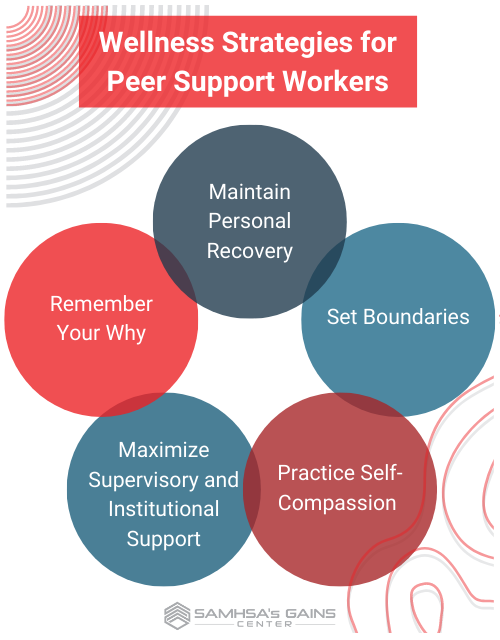

Peer support workers are a vital resource for individuals with mental and substance use disorders working to achieve and maintain recovery. Peers serve as advocates, build community and relationships, share information and connections, and support people as they make big life transitions and small steps toward recovery.[1]

Peer support increases engagement in care, improves quality of life, and reduces recidivism for individuals with justice involvement and mental and substance use disorders.[2] But peer work is not easy. It involves partnering with people navigating significant challenges, often the same challenges peers have faced. Thus, it is critically important for peers to maintain their wellness.

Recovery is a personal journey that looks different for each person. But all recovery is guided by the belief that challenges and conditions can be overcome and that a person has the strength, talents, coping abilities, resources, and inherent value to move forward from their experiences and lead meaningful and purposeful lives. The same can be true for how peer support workers maintain their well-being: while each peer’s wellness strategies may look different, they likely all call up one’s resilience, hope, and capacity to deal with difficult experiences.

The GAINS Center spoke to two peers about their wellness strategies: Philip Cooper, a certified community health worker and certified peer support specialist, who oversees a team of peer support workers providing reentry services in Western North Carolina, and Sametra Polkah-Toe, a licensed mental health counselor and certified peer specialist, who works with individuals experiencing homelessness and other life challenges in upstate New York. The following are some of their strategies for wellness and self-care.

The GAINS Center spoke to two peers about their wellness strategies: Philip Cooper, a certified community health worker and certified peer support specialist, who oversees a team of peer support workers providing reentry services in Western North Carolina, and Sametra Polkah-Toe, a licensed mental health counselor and certified peer specialist, who works with individuals experiencing homelessness and other life challenges in upstate New York. The following are some of their strategies for wellness and self-care.

Personal Recovery Maintenance

“To be successful as a peer support specialist, you must work on your own recovery,” says Cooper. “You’ve got to practice what you preach.” That includes using recovery tools that have proven effective and bringing in other strategies if circumstances or needs change. For instance, a peer support specialist who found great success with 12-step meetings while incarcerated would most likely benefit from continuing 12-step meetings when they transition to a peer support role in the community upon release. “When you’re working as a peer specialist in prison, there is a lot of peer pressure to maintain your recovery, be a role model, and bring your A-game to your work,” says Mr. Cooper. “When you leave prison, you must continue that commitment and work on it yourself. Recovery is a journey, not a destination.”

Set Boundaries

Boundaries in peer support services can help peers safeguard their own well-being. They also allow peers to model boundary-setting behaviors, supporting the development of self-advocacy skills among the people they serve. Polkah-Toe uses careful planning to protect herself physically and emotionally, which benefits the people she serves. “It sounds simple, but if I am going to be out in the community and it’s cold, for example, and I know some of the people I work with are going to have no place to stay or need a warm coat, I plan it out, how that might make me feel and how I will respond to it,” she says. “So, I think through, ‘How can I help this person navigate these challenges? What resources are available to them, like a service agency that gives out coats or a shelter with open beds?’” By recognizing the limits of her role and identifying other resources that can help meet an individual’s needs, she avoids over-extending herself, emotionally and logistically, and connects the individual with sustainable support. For Polkah-Toe, the principles of making and using a Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) are a helpful tool for protecting her own recovery in situations like this. However, she notes, any thoughtful planning will work.

Another essential boundary for some peers may be to make sure not to attend the same peer support or recovery meetings also attended by the people they serve. This provides a useful boundary to allow the peer to focus on their recovery during meetings, rather than worrying about the recovery of the person they serve or how the peer may be perceived.

Practice Self-Compassion

In a 2021 study in the Journal of Addiction and Addictive Disorders,[3] most peers reported that working with individuals in early recovery from mental or substance use disorders can be intense and challenging. Self-care is a critical component of being a peer support worker. Self-care can be any activity or practice that improves your feelings of well-being in the moment and over time. Examples include connecting with friends, participating in a hobby, making and eating a healthy meal, or going for a walk. Like recovery, self-care is unique to the person.

Similarly, self-compassion means affording oneself kindness and empathy, and it is equally important. “In my experience, peers who burn out often took on too much and became too invested in their consumers’ lives,” says Polkah-Toe. “It is easy to see yourself in those situations and want to do anything you can to help.” But Polkah-Toe often reminds the peers she supervises to give themselves the same grace and kindness they give the people they serve. She says, “I practice a mantra: ‘I am not superwoman.’ I cannot do and am not responsible for doing everything for the people I serve.” This practice keeps her work sustainable and guards against burnout.

Maximize Supervisory and Institutional Support

Effective, recovery-oriented, and person-centered supervision is essential for peer workers since, often, the job is built around personal experience and on-the-job learning. According to a 2021 study in the journal Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, peers most benefit from supervision by someone with a similar experience of recovery (e.g., individuals in recovery from substance use disorder should be supervised by other individuals in recovery from substance use disorder). Peers reported that direct supervisors with clinical expertise rather than personal experience often lacked an “understanding of the lived experience, recovery processes, the delicate balance of maintaining boundaries and personal disclosure,” in addition to “not having the deeper level of understanding recovery experiences that they were looking for” from their supervisor.[4]

This rings true for Cooper, who sees his role as supervisor as going beyond the usual administrative and organizational capacity common in other workplaces. “Peers should supervise peers,” he says. “And, as a supervisor, one of the things I check in on my staff is how they are working on their recovery and taking steps to keep themselves well. If you are qualified to do your job because of your recovery, then part of your professional development includes maintaining your recovery.”

Additionally, some workplaces, like Mr. Cooper’s, offer time allowances for peers to attend recovery meetings during the day or have mental health days built into a benefits package. (For more ideas on how to support recovery in the workplace, see the U.S. Department of Labor’s Recovery-Ready Workplace Resource Hub.) Polkah-Toe notes that she encourages the peers that she supervises to use the resources available through their employer, such as an employee assistance programs and paid time off. Other strategies can include supporting peers in developing a WRAP plan for the workplace (to complement their personal WRAP plan) and educating staff on ways to request accommodations when their work may become too overwhelming or may prompt a recurrence of unwanted symptoms or behaviors. Another option is encouraging staff to have their own “toolkit” of strategies and physical items that can support their wellbeing, which may include their WRAP plan or a similar plan for addressing situations that may provoke challenging thoughts, feelings, or behaviors; small gift cards to a nearby coffee shop for when staff might need to step away briefly for a quiet moment; small, grounding stones or objects inscribed with a meaningful mantra or word; items infused with a grounding or calming scent; photos of supportive loved ones; and more. Building a work community where peers feel comfortable sharing their experiences with one another and navigating the stressors that come with the work together can help peers increase their sense of connection and reduce risks that can come from isolation and overwhelm.

Remember Your Why

Many peer specialists choose their job because they want to share their experiences and help others achieve and maintain their recovery. Remembering your essential contribution to others’ success can help prevent burnout and keep peer support specialists motivated through difficult work. “I believe in recovery out loud. I encourage peer workers to fall in love with the journey and proudly tell people about it,” says Cooper. “I openly spread the message of hope, healing, and recovery through my work and community. My predecessors taught me that the only way to keep what I have is by giving it away to others.”

[1] SAMHSA, Bringing Recovery Supports to Scale, “Peer Support Workers for Those in Recovery,” accessed February 6, 2023, https://www.samhsa.gov/brss-tacs/recovery-support-tools/peers.

[2] National Institute of Corrections, From Recidivism to Recovery: The Case for Peer Support in Texas Correctional Facilities (Austin: Center for Public Policy Priorities, 2014).

[3] Christian Williams, “To Help Others, We Must Care for Ourselves: The Importance of Self-Care for Peer Support Workers in Substance Use Recovery,” Journal of Addiction & Addictive Disorders 8, no. 2 (December 24, 2021): 1–7, https://doi.org/10.24966/AAD-7276/100071.

[4] Christian Scannell, “Voices of Hope: Substance Use Peer Support in a System of Care,” Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment 15 (January 2021): 117822182110503, https://doi.org/10.1177/11782218211050360.