By Douglas B. Marlowe, JD, PhD, National Association of Drug Court Professionals

No program or intervention can be expected to work for everyone. Providing too much or the wrong kind of services not only fails to improve outcomes, but it can make outcomes worse by placing excessive burdens on some participants and interfering with their engagement in productive activities, like work or school. This is the foundation for a body of evidence-based principles referred to as risk, need, responsivity, or RNR (Andrews & Bonta, 2010). RNR is derived from decades of research demonstrating that the best outcomes are achieved in the criminal justice system when (1) the intensity of criminal justice supervision is matched to participants’ risk for criminal recidivism or likelihood of failure in rehabilitation (criminogenic risk) and (2) interventions focus on the specific disorders or conditions that are responsible for participants’ crimes (criminogenic needs) (Andrews et al., 1990, 2006; Gendreau et al., 2006; Lipsey & Cullen, 2007; Lowenkamp et al., 2006a, 2006b; Smith et al., 2009; Taxman & Marlowe, 2006). Moreover, mixing participants with different levels of risk or need in the same treatment groups or residential programs has been found to increase crime, substance use, and other undesirable outcomes, because it exposes low-risk participants to antisocial peers and values (e.g., Lloyd et al., 2014; Lowenkamp & Latessa, 2004; Lowenkamp et al., 2005; Welsh & Rocque, 2014; Wexler et al., 2004).

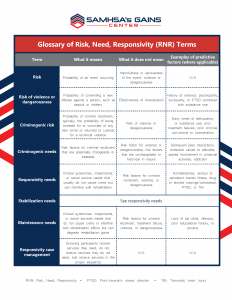

Despite compelling evidence validating these RNR principles, many behavioral health and criminal justice professionals misconstrue the concepts of risk, need, and responsivity, leading them to deliver the wrong services to the wrong persons and in the wrong order. Even with the best of intentions to follow evidence-based practices, many programs inadvertently waste precious resources, frustrate consumers, and deliver lackluster results. To enhance program effectiveness and efficiency, it is necessary to translate these research-based principles into terms that are familiar to many practitioners, to help them select the most appropriate interventions under the right circumstances. [To aid in this process, a glossary of technical terms used in this article is provided in Table 1.]

TABLE 1: Glossary of RNR Terms

|

Term |

What it Means | What it Does Not Mean |

Examples of Predictive Factors (Where Applicable) |

| Risk | Probability of an event occurring | Harmfulness or seriousness of the event; violence or dangerousness | N/A |

| Risk of violence or dangerousness | Probability of committing a new offense against a person, such as assault or robbery | Effectiveness of incarceration | History of violence, psychopathy, or sociopathy, or PTSD combined with substance use |

| Criminogenic risk | Probability of criminal recidivism; typically, the probability of being arrested for or convicted of any new crime or returned to custody for a technical violation | Risk of violence or dangerousness | Early onset of delinquency or substance use, prior treatment failures, prior criminal convictions or incarceration |

| Criminogenic needs | Risk factors for criminal recidivism that are potentially changeable or treatable | Risk factor for violence or dangerousness, risk factors that are unchangeable or historical in nature | Delinquent peer interactions, antisocial values or attitudes, sparse involvement in prosocial activities, addiction |

| Responsivity needs | Clinical syndromes, impairments, or social service needs that usually do not cause crime but can interfere with rehabilitation | Risk factor for criminal recidivism, violence, or dangerousness | Homelessness, serious or persistent mental illness, drug or alcohol cravings/withdrawal, PTSD, TBI |

| Stabilization needs | See responsivity needs | See responsivity needs | See responsivity needs |

| Maintenance needs | Clinical syndromes, impairments, or social service needs that do not cause crime or interfere with rehabilitation efforts but can degrade rehabilitation gains | Risk factor for criminal recidivism, treatment failure, violence, or dangerousness | Lack of job skills, illiteracy, poor educational history, poverty |

| Responsivity case management | Ensuring participants receive services they need, do not receive services they don’t need, and receive services in the proper sequence | N/A | N/A |

RNR: Risk, Need, Responsivity. PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder. TBI: Traumatic brain injury

What is Risk?

For researchers, the term risk refers to probability or likelihood. High risk indicates that an event is more likely to occur than by chance or on average, and low risk indicates it is less likely to occur. In most instances, it does not refer to the seriousness or harmfulness of the event. Most risk assessment tools used in the criminal justice system were validated against the probability that test takers will be arrested for, or convicted of, any new criminal offense or returned to custody for a technical violation[1] (see top of Table 2 for examples of such tools). Therefore, if one person has a 60 percent chance of being arrested for drug possession and another has a 10 percent chance of being arrested for assault, the first person is likely to score higher on most commonly administered risk assessment tools. Unless a program employs a tool specifically validated for risk of violence or dangerousness (bottom of Table 2), it is unwarranted to assume that a high score equates to a threat to public safety, program personnel, or fellow participants.

[1] A technical violation is not necessarily a crime per se, but may violate a court, probation, or parole condition. For example, drinking alcohol is legal for most adults but may be a technical violation of probation.

TABLE 2: Examples of Commonly Administered Risk Assessment Tools

| Type of Risk | Risk Assessment Tool |

| Risk of General Recidivism, Technical Violations, and/or Failure on Community Supervision |

|

| Risk of Violence or Dangerousness |

|

Most importantly, no study has yet determined what risk scores, if any, predict better outcomes in jail or prison as opposed to community-based dispositions, such as probation or treatment court. For this reason, risk scores should never be used to decide who should be incarcerated and who should receive a community sentence. At most, information garnered from these tools should be used to set conditions of treatment and supervision for persons involved in the criminal justice system.

Unfortunately, many practitioners and policy makers wrongly equate risk with a likelihood of violence, dangerousness, or other serious criminal offense. As a result, many programs exclude high-risk persons from intensive treatment-oriented services and target low- or moderate-risk persons for those services. This is precisely the wrong strategy. High risk means that individuals are unlikely to desist from crime unless they receive intensive services and low risk means they are apt to abstain on their own. It makes little sense to deny services to the persons who need them the most and target those services to persons who do not require them.

For behavioral health providers, risk is essentially analogous to the clinical or medical concept of prognosis. Patients with a poor or complicated prognosis have known risk factors (e.g., a history of smoking or high blood pressure) that make them less likely to respond to standard treatments; therefore, clinicians tend to treat them more aggressively. Physicians may, for example, prescribe higher doses of medication for high-risk patients, perform surgery, or recommend radiation or chemotherapy. On the other hand, physicians usually do not prescribe aggressive treatments for patients with a favorable prognosis because they are unlikely to benefit from the additional services and may experience unwarranted side effects. This would waste precious resources and make some patients worse off.

It behooves criminal justice and behavioral health professionals to check their gut instincts at the door and give pause whenever they hear the term risk. Rather than excluding high-risk persons from our programs, we should be targeting those individuals for our services. Risk nevertheless does have critical implications for case planning. The higher a person’s risk level, the less likely he or she will seek treatment voluntarily and remain in treatment long enough to achieve therapeutic aims (Olver et al., 2011). Therefore, high-risk persons will often require enhanced structure and accountability to ensure they engage appropriately in treatment and comply with the services offered. High-risk persons may, for example, need to appear frequently in court for a judge to review their progress in treatment, meet regularly with a probation or parole officer, undergo random drug and alcohol testing, and receive gradually-escalating incentives for achievements in treatment and sanctions for infractions. Supervision officers may also need to conduct periodic home or employment visits for high-risk persons to enforce conditions of supervision, such as curfews or geographic restrictions, and monitor signs of impending relapse, such as a disheveled home environment or drug paraphernalia in the home. Treatment professionals and criminal justice professionals must work closely together to co-manage high-risk cases, share relevant information, and coordinate their efforts to ensure that persons most in need of treatment can realize the benefits of those services.

What is Need?

The term need has very different meanings for criminal justice professionals, behavioral health treatment providers, and social service providers. Pursuant to classical RNR principles, most criminal-justice professionals bifurcate needs into two broad categories: (1) criminogenic needs and (2) non-criminogenic needs. Criminogenic needs are essentially dynamic or alterable risk factors for criminal recidivism. Some risk factors, such as an early age of onset of delinquency, are historical in nature and cannot be modified through criminal justice interventions. Others, however, can be ameliorated through correctional programming, such as reducing participants’ interactions with delinquent peers or addressing antisocial attitudes. Other problems or disorders encountered frequently in criminal justice populations, such as low self-esteem or depression, are referred to as non-criminogenic because they are most often a result rather than the cause of crime. Treating non-criminogenic needs before treating criminogenic needs has been associated with negative outcomes, including higher rates of criminal recidivism, substance use, and unemployment (Andrews & Bonta, 2010; Andrews et al., 1990; Smith et al., 2009; Vieira et al., 2009).

Treatment providers and social service professionals are frequently perplexed by this narrow taxonomy of need. For treatment providers, need typically refers to conditions like mental health disorders, substance use disorders, or cognitive impairments. For social service professionals, need typically refers to housing instability, poverty, lack of basic job skills, or low education. Although most of these clinical and social service needs are not criminogenic (meaning they are usually not a principal cause of crime), they nevertheless can interfere substantially with other rehabilitation efforts. For example, criminal justice professionals are likely to have a very difficult time addressing a participant’s antisocial attitudes or delinquent peer interactions if he or she is living on the street, suffering from a severe mental illness, or experiencing acute withdrawal symptoms from drugs or alcohol. Ignoring or delaying attention to these concerns is not a realistic course of action if one wishes to reduce crime and rehabilitate criminal justice-involved persons. Considerably more clarity and precision are required to usefully classify the heterogeneous array of non-criminogenic needs.

Some non-criminogenic needs, such as homelessness or severe mental illness, are likely to interfere with a participant’s response to correctional rehabilitation efforts and must be stabilized early before other interventions can proceed. Referred to as responsivity needs or stabilization needs, they are an important exception to the rule that criminogenic needs should be treated before non-criminogenic needs and must be addressed early in treatment to allow other interventions to take hold (Hubbard & Pealer, 2009; Peters et al. 2015; Prins et al., 2015; Skeem et al., 2015). Other needs, such as illiteracy or deficient job skills, are unlikely to improve until after participants have been stabilized clinically, abstained from criminal activity, and reduced or eliminated their interactions with delinquent peers. Focusing prematurely on these issues is apt to overburden participants and could interfere with their engagement in more pressing obligations, such as attending counseling sessions and probation appointments. Left unaddressed long term, however, these needs are likely to seriously undermine any therapeutic progress that has been achieved and precipitate relapse to crime, substance use, or other undesirable behaviors. Referred to as maintenance needs, they must be addressed in due course to ensure that participants continue to practice the skills they have learned in treatment and consolidate the gains they have made.

Although many of the tools listed in Table 2 purport to measure both risk and need factors, most of them largely ignore or gloss over responsivity and maintenance needs. As a result, criminal justice professionals are often unaware of why their interventions are not working. For example, failing to recognize serious mental health or substance use disorders in their clients, they may revoke their probation or deliver punitive sanctions when noncompliance was a symptom of distress rather than willful misconduct. And, when criminal justice professionals do recognize these needs in their clients, they often refer them to other community service agencies for assessment and treatment. Clinicians and supervision officers may then find themselves working at cross purposes, placing excessive, duplicative, or inconsistent demands on the most vulnerable and impaired individuals who are least capable of meeting those demands.

Effective case planning requires criminal justice and behavioral health professionals to assess the full range of criminogenic, responsivity, and maintenance needs presented by their clients and deliver indicated treatment, supervision, and social services accordingly. Artificially partitioning needs into separate domains to be addressed piecemeal by different agencies contributes to gross inefficiency and confusion in service provision. This is where responsivity, often the most overlooked component of RNR, attains critical significance.

What is Responsivity?

Responsivity is analogous to treatment planning and clinical case management in the health professions. The principal goals are to ensure that participants receive the services they need, do not receive more services than they need, and receive services in the most effective and efficient sequence. Leaving pressing problems unaddressed allows them to fester and worsen, delivering unnecessary services can overburden participants and interfere with their engagement in required services, and addressing responsivity needs, criminogenic needs, or maintenance needs in the wrong order is likely to undermine the effectiveness of the interventions.

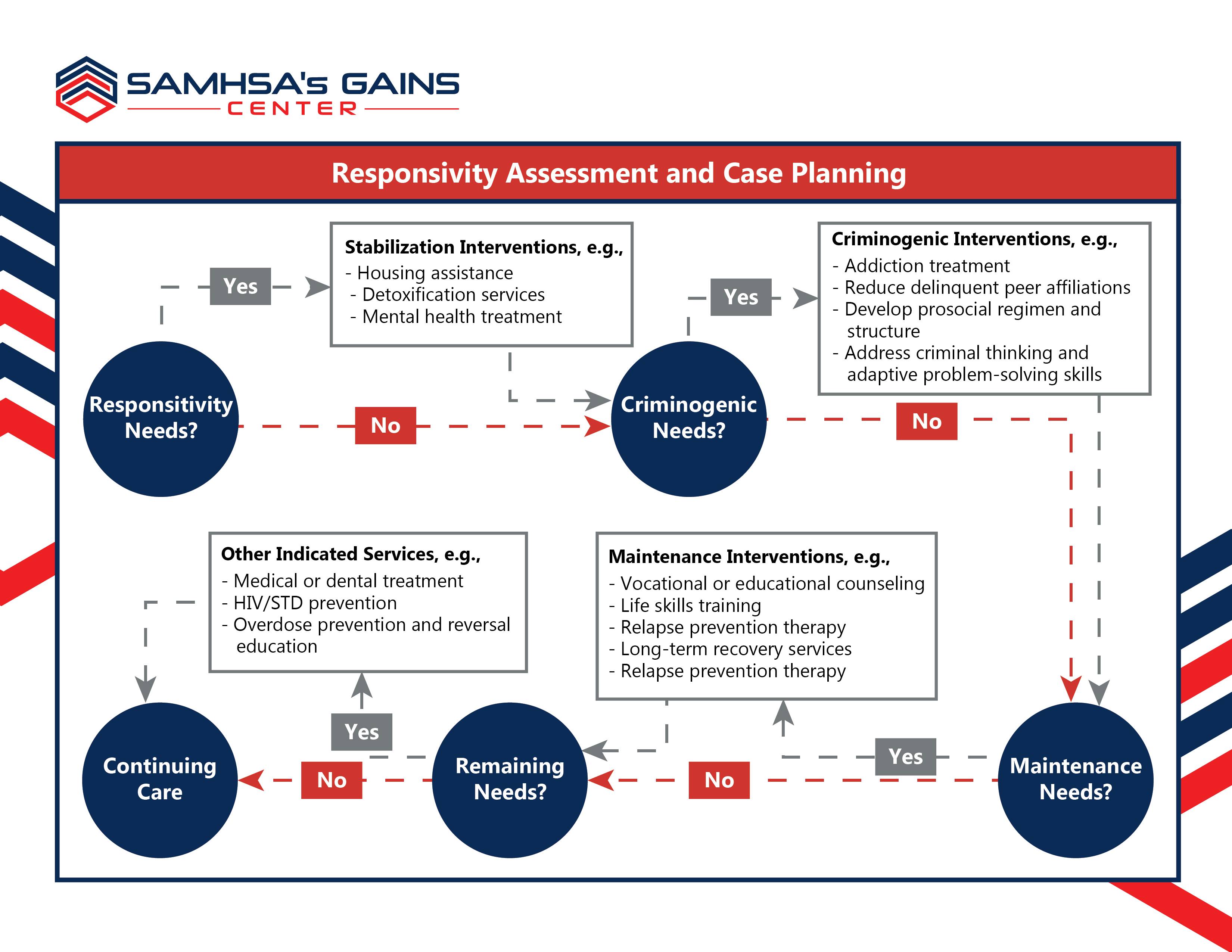

Figure 1 depicts a decisional flowchart for applying responsivity principles in criminal justice case management. The first stage in the process involves assessing and, if necessary, resolving, conditions that are likely to interfere with retention or compliance in rehabilitation (responsivity needs). This may include meeting participants’ basic housing needs, stabilizing mental health symptoms, or treating acute psychological or physiological symptoms of addiction, such as cravings or withdrawal. The second stage addresses factors that increase the likelihood of criminal recidivism, such as addiction, delinquent peer interactions, and antisocial attitudes (criminogenic needs). The third stage addresses maintenance concerns, such as illiteracy or lack of vocational skills (maintenance needs). Subsequently, clinicians may address other unmet service needs that affect participants’ health and welfare, such as health-risk behaviors and medical or dental problems. Finally, because many programs will not have legal jurisdiction over participants long enough to deliver the entire sequence of indicated services, case managers must develop continuing-care plans to pick up seamlessly where criminal justice services left off and ensure that participants achieve long-term success and maintenance of treatment effects.

Accomplishing these complicated tasks requires the knowledge and skills of a professionally trained clinical case manager who is competent to perform or interpret the results of criminogenic risk assessments and clinical and social service evaluations, understands how services should be sequenced and matched to the identified needs, and can monitor and report on participant progress (Cook, 2002; Maume et al., 2018; Rodriguez, 2011). Typically, such case managers are social workers or psychologists employed by treatment agencies working alongside the justice system; however, clinically-credentialed employees of probation or parole departments can also perform such functions if they have received the appropriate training.

Needless to say, many criminal justice programs do not have these essential personnel on staff or available through contractual arrangements. Rectifying this deficiency should be the first order of business for any program attempting to apply evidence-based practices and improve criminal justice outcomes. No intervention can be said to be “evidence-based” unless it has been matched carefully to the assessed needs and risk levels of participants and delivered in the appropriate sequence. Programs that believe they have accomplished their goals by sending staff members to trainings on specific interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or motivational interviewing, do not understand what it means to be evidence-based. Not having a clinical case manager available who is trained in responsivity principles is like purporting to treat cancer without an oncologist. The tasks are too complicated and the stakes too high.

References

Andrews, D.A., & Bonta, J. (2010). The psychology of criminal conduct (5th ed.). New Providence, NJ: Anderson.

Andrews, D.A., Bonta, J., & Wormith, J.S. (2006). The recent past and near future of risk and/or need assessment. Crime & Delinquency, 52(1), 7–27.

Andrews, D.A., Zinger, I., Hoge, R.D., Bonta, J., Gendreau, P., & Cullen, F.T. (1990). Does correctional treatment work? A clinically relevant and psychologically informed meta-analysis. Criminology, 28(3), 369–404.

Cook, F. (2002). Treatment accountability for safer communities: Linking the criminal justice and treatment systems. In C.G. Leukefeld, F. Tims, and D. Farabee (Eds.), Treatment of drug offenders: Policies and issues (pp. 105–110). New York: Springer.

Gendreau, P., Smith, P., & French, S. A. (2006). The theory of effective correctional intervention: Empirical status and future directions. In F. T. Cullen, J. P. Wright, & K. R. Blevins (Eds.), Taking stock: The status of criminological theory (vol. 15). Advances in criminological theory (pp. 419–446). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Hubbard, D.J., & Pealer, J. (2009). The importance of responsivity factors in predicting reductions in antisocial attitudes and cognitive distortions among adult male offenders. Prison Journal, 89(1), 79–98.

Lipsey, M. W., & Cullen, F. T. (2007). The effectiveness of correctional rehabilitation: A review of systematic reviews. Annual Review of Law & Social Science, 3, 279–320.

Lloyd, C.D., Hanby, L.J., & Serin, R.C. (2014). Rehabilitation group coparticipants’ risk levels are associated with offenders’ treatment performance, treatment change, and recidivism. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 82(2), 298–311.

Lowenkamp, C.T., & Latessa, E.J. (2004). Understanding the risk principle: How and why correctional interventions can harm low-risk offenders. Topics in Community Corrections, 2004, 3–8.

Lowenkamp, C.T., & Latessa, E.J. (2005). Increasing the effectiveness of correctional programming through the risk principle: Identifying offenders for residential placement. Criminology & Public Policy, 4(2), 263–290.

Lowenkamp, C.T., Latessa, E.J., & Holsinger, A.M. (2006a). The risk principle in action: What have we learned from 13,676 offenders and 97 correctional programs? Crime & Delinquency, 52(1), 77-93.

Lowenkamp, C.T., Pealer, J., Smith, P., & Latessa, E.J. (2006b). Adhering to the risk and need principles: Does it matter for supervision-based programs? Federal Probation, 70(3), 3–8.

Maume, M.O., Lanier, C., & DeVall, K. (2018). The effect of treatment completion on recidivism among TASC program clients. International Journal of Offender Therapy. Doi: 10.1177/0306624X18780421.

Olver, M.E., Stockdale, K.C., & Wormith, J.S. (2011). A meta-analysis of predictors of offender treatment attrition and its relationship to recidivism. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 79(1), 6–21.

Peters, R.H., Wexler, H.K., & Lurigio, A.J. (2015). Co-occurring substance use and mental disorders in the criminal justice system: A new frontier of clinical practice and research. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(1), 1–6.

Prins, S.J., Skeem, J.L., Mauro, C., & Link, B.G. (2015). Criminogenic factors, psychotic symptoms, and incident arrests among people with serious mental illnesses under intensive outpatient treatment. Law & Human Behavior, 39(2), 177–188.

Rodriguez, P.F. (2011). Case management for substance abusing offenders. In C. Leukefeld, T.P. Gullotta & J. Gregrich (Eds.), Handbook of evidence-based substance abuse treatment in criminal justice settings (pp. 173–181). New York: Springer.

Skeem, J.L., Steadman, H.J., & Manchak, S.M. (2015). Applicability of the risk-need-responsivity model to persons with mental illness involved in the criminal justice system. Psychiatric Services, 66(9), 916–922.

Smith, P., Gendreau, P., & Swartz, K. (2009). Validating the principles of effective intervention: A systematic review of the contributions of meta-analysis in the field of corrections. Victims & Offenders, 4(2), 148–169.

Taxman, F.S., & Marlowe, D.B. (Eds.) (2006). Risk, needs, responsivity: In action or inaction? (Special issue). Crime & Delinquency, 52(1).

Vieira, T.A., Skilling, T.A., & Peterson-Badali, M. (2009). Matching court-ordered services with treatment needs: Predicting treatment success with young offenders. Criminal Justice & Behavior, 36(4), 385–401.

Welsh, B.C., & Rocque, M. (2014). When crime prevention harms: A review of systematic reviews. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 10(3), 245–266.

Wexler, H.K., Melnick, G., & Cao, Y. (2004). Risk and prison substance abuse treatment outcomes: A replication and challenge. The Prison Journal, 84(1), 106–120.

Footnotes

[1] A technical violation is not necessarily a crime per se, but may violate a court, probation, or parole condition. For example, drinking alcohol is legal for most adults but may be a technical violation of probation.