The GAINS Center’s Learning Collaboratives Recap Series

States across the country are experiencing increased demand for competency evaluations, but competency evaluation and restoration programs frequently have too few beds to meet the needs of those found incompetent to stand trial (IST). This leaves many clients and cases in limbo until space becomes available. SAMHSA’s GAINS Center’s Competency to Stand Trial/Competency Restoration Learning Collaborative (LC) was an initiative designed to help states address this situation, to identify best practices for competency evaluation and restoration programs, and to build collaborations between state and local agencies. The GAINS Center hosted all LC activities and provided virtual meeting coordination, conference calls, and in-person technical assistance from GAINS Center staff and subject-matter experts free of charge. While this LC has only been active for a few months, some key takeaways have become clear.

The Competence Process Is a State Issue

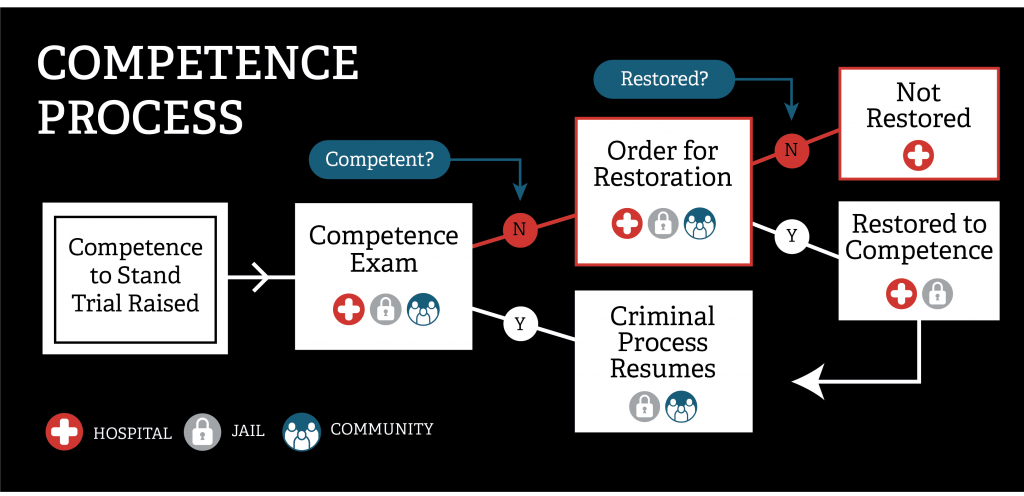

Addressing competency issues requires state-level involvement, not just local communities, because the laws about competency as well as any financial responsibility lie with the state. Many states have competence processes that pose a range of challenges. The “competence process” comprises the issue being raised by a judge or attorney; an order by a judge for a competency evaluation; a finding by the judge— based on the clinical evaluation—of competency or incompetency to stand trial; a judicial order for competency restoration when IST; and case disposition.

Please click here for a text alternative to this graphic.

When a prosecutor, public defender, or judge raises competency, the “pause button” is hit on the criminal justice process. Individuals remain the responsibility of the state because they have been arrested, but the state has decided they cannot be tried until their competency to participate in their proceedings has been determined and is restored if found IST. Unfortunately, the process can stay “paused” for a long time and for any charge, no matter how minor. Some states have tried to calibrate their systems based on the severity of the crime, while others have tried to divert those with misdemeanors from the system altogether. But generally, everyone with competency issues is treated the same, often waiting in jail for evaluation and restoration, if found IST, for longer than they would serve in jail if convicted.

Improving the competence processes is complex and requires the involvement of specific authorities, such as an administrative or state court judge, the state forensic director, and potentially the state legislature, among others. This is because competency affects people who have not yet entered a plea, meaning that changes in the affected parts of the system require changes in the law in some instances and change in local practice for other types of changes. Although local criminal justice staff, like sheriffs, often feel the effects of deficiencies in how competency is handled, the power to improve the process remains to a great extent with the state. And to solve such a large state issue, people with some authority who could realistically help implement changes must be involved.

The Clinical and Legal Systems Must Work Together

Though ordering a competency exam is often exclusively a legal question, the competency evaluation and restoration processes can only be improved by the clinical and legal systems working together. Both systems play significant roles at different phases of the competency process, but a common lack of cross-systems knowledge frequently leads to unintended consequences. Judges who order a competency evaluation receive little or no training on appropriate use of competency evaluations and are not required to consult with a psychiatrist or social worker prior to ordering an exam. Some judges may order competency exams as a way to get people into treatment without realizing that the jail where the individuals awaiting evaluation are held may not offer appropriate services. As a result, these individuals’ illnesses may worsen, regardless of the judge’s good intentions.

Competency evaluations are performed by a wide range of clinical experts in terms of their training and expertise. If the evaluator deems an individual IST, the individual is handed over for clinical treatment and legal education, often at a state hospital. Hospitals are the most sought-after provider of competency restoration, but several factors make them an imperfect competency restoration solution for the increasing number of people awaiting the process. Hospital competency restoration is the most expensive form of restoration; due to cost pressures, there are not currently and likely never will be enough hospital beds to meet the demand. Further, even when, after a long wait, individuals are sent to a state hospital (rather than receiving treatment in jail or in the community), their ability to move forward following restoration is uncertain. In most states, a defendant can return to court and proceed with the pending charges after being restored to competency when the judge issues the order, regardless of when the clinician concluded the defendant was ready. Typically judges (and sometimes even public defenders) contradict the competency assessment of clinicians at this phase to keep individuals in hospital-based treatment. But doing so after an individual is clinically restored to competency prolongs this part of the individual’s involvement in the justice system and takes up scarce hospital space, extending already lengthy wait-lists for treatment for others. Common issues such as these can only be addressed when the clinical and legal systems work together to improve the competency process.

Small Changes—and a Little Information-Sharing—Make a Big Difference

For many state leaders who want to advance competence process improvements but do not know where to start, it can be incredibly energizing simply to hear that they are not alone and that other states have the same or similar issues. This was one of the greatest strengths of the LC: giving a sense of purpose to participants and encouraging them to believe they can make meaningful changes. As a result of this collaboration, participants became aware of systems and strategies used in other states that they had never considered before, such as diverting people with misdemeanors out of the competence process.

Significant information-sharing took place among sites participating in this LC. For example, one site shared how it changed policy to allow its state hospitals to send people back to jail after being restored without approval from the judge. This change completely altered the way criminal justice professionals viewed the state hospitals. The hospitals were no longer seen as places where justice-involved people with competency issues could be off-loaded and held for any period of time; it was now up to the jails to figure out how to proceed once peoples’ competency was restored. This seemingly small change to who played gatekeeper on the way out of the hospital after restoration was transformative. Many participants in the LC were inspired by this example and came to believe that they could implement the same change.

By the end of the experience, all states had made progress on their goals and were enthusiastic to continue this work next year, leveraging the individual participants’ roles as state officials who can make decisions and advocate for change. Some states even began communicating with each other beyond the virtual meetings and conference calls facilitated by the GAINS Center, perfectly exemplifying what it means to be a part of a collaborative.

Further Topics

This article captures a few key takeaways from the GAINS Center’s 2019 Competency to Stand Trial/Competency Restoration Learning Collaborative, but there are many other important aspects of states and localities working together to effectively address competency issues. If you have additional questions regarding this topic, please reach out to us here at the GAINS Center with your inquiries.